Anatomy of Iran's Internet

I’m slightly addicted to reading the news but I often forget about the Gell-Mann amnesia effect. This describes the phenomenon where if you’re an expert in a field you can spot lots of errors and problems with news articles in your given field but return to absolute trust once you read another article within a field you know nothing about. The subjects of network infrastructure and border gateway protocol (BGP) are not often closely examined in most newspapers so I’m usually in a state of blissful ignorance.

However, with the recent prolonged shutdown of Iran’s internet amid national protests1 there were repeated descriptions of some sort of national kill switch deployed by the government. This evokes an image of a giant industrial switch in a datacenter that gets dramatically switched once a call is received on the nearby red phone. While this makes for a good headline, it reduces the nuances of modern network infrastructure to a caricature. To be fair to some journalists, such as Mehul Srivastava and Chris Campbell, there exists some reporting that is technically very much on point.2

But does the nuance in this particular case matter? I think it matters quite a bit, mostly because this national strategy is very similar to what has already been deployed in China and Russia, among other internet restricted nations. It threatens the underlying notion of an unrestricted public internet where governments can shape and suppress their citizens access to information and ability to participate in civic dialogue. Awareness of the architecture of your suppression doesn’t make you any less suppressed but it certainly presents you with more options than ignorance.

National Information Network

To explore the details a bit further we have to go back to the formation of Iran’s National Information Network (NIN). Understanding Iran’s current internet architecture requires an examination of this network. It establishes the regime’s view of the global internet as an adversarial and hostile territory.

The NIN architectural framework involves two major design points. The first was a sovereign national intranet that formed an internal network within the confines of Iran. Cut off from the wider international internet, this intranet would offer services and function under the control of state regulations. The second design required a complete and total aggregation of international gateways to entities controlled by the government. Consolidating this connectivity ensures that citizens access only government-approved international content.

To understand the anatomy of the internet in Iran you have to abandon the Western conception of the World Wide Web as a global commons, public utility, or even the endeavor of a private company. Leaving the task of connecting your citizens across international borders to a variety of private companies is both inefficient and fractious if your primary goal is information control.

In the pragmatic approach of the Islamic Republic, the internet is viewed primarily as a contested territory and is a domain of conflict where losing the battle of information warfare is a threat to the stability of the state. The system is designed to resolve the authoritarian dilemma of how to harvest the economic benefits of digital connectivity without importing the political risks of the open web.

The architecture relies on a fundamental bifurcation between the international internet, a heavily filtered bridge to the outside world, and the NIN, a hermetically sealed domestic intranet. This design allows the state to throttle or filter international connections during unrest. Meanwhile, the domestic intranet remains operational for banking, administrative services, and internal propaganda. The NIN is a digital fortress built to keep foreign culture out and to entrap the Iranian population within a controllable digital environment.

The architectural proposal for the NIN was spoken about in the early 2000s but didn’t take off in adoption and implementation until after the protests of the disputed 2009 presidential election.3 During the 2009 Green Movement, where protesters utilized platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and SMS messaging to organize against the disputed re-election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Iranian officials began to see the influence of the international internet as a source of vulnerability4 for state control. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei later codified Iran’s official view, claiming that Western digital influence was a cultural invasion designed to undermine Iran.5 This led to the reinforcement of the regime’s ideology that relying on Western communication infrastructure was an intolerable national security vulnerability, and only further motivated the adoption of the NIN architecture to create a localized internet.

During the early deployment of the NIN, officials described its purpose in moralistic, benign terms. Building the NIN was about establishing a “pure” internet that was “free from immoral, corrupt, and violent content.”6 In tandem to this pure internet there would also be the international internet, which citizens would still have access. In hindsight this was patently false.

Another interesting point of the early days of NIN deployment was research done by Collin Anderson and colleagues in Iran were their mapping of the growing intranet inside Iran in late 2012.7 Much of the address space used by intranet assets were within RFC 1918 IP address space. In Mr. Anderson’s research he was able to map out several government, telecommunications, and academic assets within the country’s internal infrastructure. This does not necessarily prove anything behind the political intentions of the NIN in 2012 but simply shows it was growing rapidly.

| Domain | IP Address | Ownership |

|---|---|---|

| lib.atu.ac.ir | 10.24.96.14 | Allameh Tabatabaie University |

| mdhc.ir | 10.30.5.163 | Vice Presidency for Management Development and Human Capital |

| iranmardom.ir | 10.30.5.148 | Vice Presidency for Management Development and Human Capital |

| erp.msrt.ir | 10.30.55.29 | Ministry of Science, Research and Technology |

| ou.imamreza.ac.ir | 10.56.51.27 | Imam Reza University |

| tehranedu.ir | 10.30.95.7 | Tehran Education Organization |

| sanaad.ir | 10.30.170.142 | Private Individual |

| ww3.isaco.ir | 10.21.201.50 | Iran Khodro Spare Parts & After-sales Services Company |

| iiees.ac.ir | 192.168.8.9 169.254.78.139 194.227.17.14 | International Institute of Earthquake Engineering and Seismology |

| tci-khorasan.ir | 10.10.3.2 217.219.65.5 10.1.2.0 | Telecommunication Company of Iran, Khorasan |

| adsl.yazdtelecom.ir | 10.144.0.14 | Telecommunications Company of Iran, Yazd |

| iranhrc.ir | 46.36.117.51 10.30.74.3 | Private Individual |

| acc4.pishgaman.net | 81.12.49.108 10.8.218.4 | Pishgaman, ADSL Access Provider |

| lib.uma.ac.ir | 10.116.2.5 | University of Mohaghegh Ardabili |

| film.medu.ir | 10.30.170.110 | Ministry Of Education |

| shirazedc.co.ir | 10.175.28.172 | Shiraz Electric Distribution Company |

While the initial driver for building the NIN was political censorship it didn’t start getting momentum until the presidency of Hassan Rouhani from 2013–2021 due to economic necessity. Paradoxically, the moderate Rouhani administration accelerated the NIN’s development more effectively than its hardline predecessors. By investing heavily in local data centers and Internet Exchange Points (IXPs), they improved connection speeds and stability for domestic traffic. To incentivize adoption, Iran mandated a price differentiation policy: bandwidth for domestic NIN traffic is sold at a fifty percent discount compared to international traffic.8 These measures fostered an environment for domestic technology growth that is apparent with the number of applications and services available to Iranians that were intended to be a substitute to their international counterparts.9

Architecture

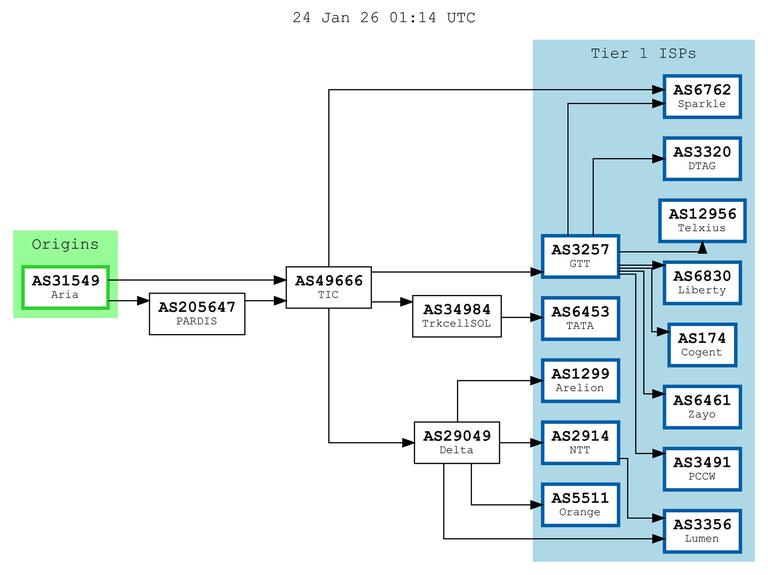

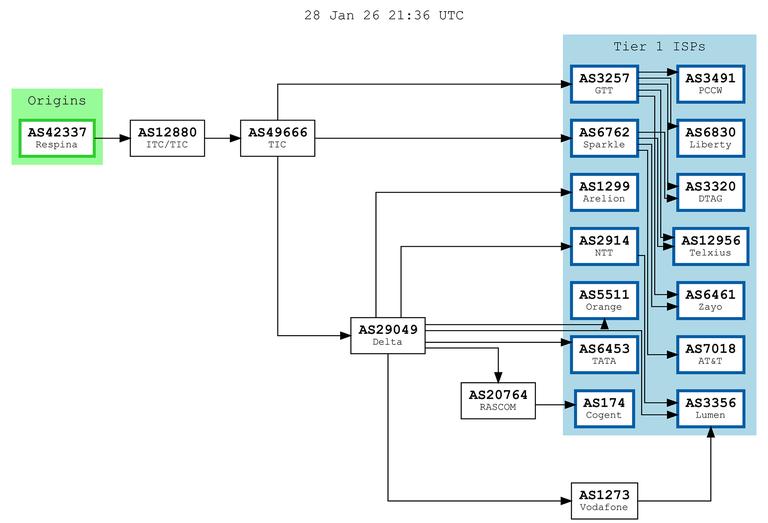

The physical reality of Iran’s internet is defined by extreme centralization. At the apex of this funnel sits the Telecommunication Infrastructure Company (TIC). This state-owned enterprise under the Ministry of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) holds a legal monopoly on all international bandwidth, acting as the sole importer and wholesaler of internet capacity.10 No private ISP in Iran, whether it be Shatel, Pars Online, or AsiaTech, can purchase bandwidth directly from a foreign carrier.11 All international bandwidth has to come from the TIC.

The only other entity at this funnel apex is through a lab at the Institute for Research in Fundamental Sciences (IPM) as part of the Ministry of Science, Research, and Technology.12 While this lab has the only other international gateway in the country, it primarily serves academic and research oriented downstream autonomous systems while TIC serves more generalized downstream clients. This consolidated architecture ensures that Iran maintains absolute control at the few international gateways where internet connectivity crosses the national border.

In 2020 there were some brief exceptions to this centralization rule. There were actually 2 autonomous systems that had their own international gateway connections independent of the TIC.13 However, both AS31549 and AS60976 have since been repatriated behind a TIC international gateway. The Article 19 organization was unable to determine why this move toward decentralization was occurring at the time. Regardless, it has since been normalized back to the status quo.

Centralization of Iran’s internet can be viewed by anyone in the world with some minor border gateway protocol (BGP) knowledge. This is the mechanism for how the modern internet is stitched together across an impressive amount of separate autonomous systems (AS). The fundamental architecture of the NIN requires all downstream AS to get their upstream internet connectivity through state owned entities. This approximately means that any AS you locate in Iran will eventually have connectivity through either TIC or IPM before it reaches any portion of the international internet. The so called funnel apex for the country.

If I take the top ten AS located in Iran, as rated by cone size, we can see this centralization in action. For clarification, cone size refers to the amount of downstream AS from a specific AS. This usually approximately indicates the importance and type of network of a particular AS.

| AS | Name | Peer Rank | AS Cone Rank | Upstream AS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS49666 | Telecommunication Infrastructure Company | #12 (19) | #1 (580) | External |

| AS12880 | Iran Information Technology Company PJSC | #12 (19) | #2 (261) | External |

| AS41689 | Asiatech Data Transmission company | #23 (2) | #3 (259) | AS49666 |

| AS43754 | Asiatech Data Transmission company | #4 (80) | #4 (258) | AS49666 |

| AS42337 | Respina Networks & Beyond PJSC | #2 (143) | #5 (224) | AS49666 |

| AS58224 | Iran Telecommunication Company PJS | #3 (96) | #6 (104) | AS49666 |

| AS49100 | Pishgaman Toseeh Ertebatat Company | #5 (36) | #7 (65) | AS41689 |

| AS25184 | Afranet | #6 (35) | #8 (56) | AS49666 |

| AS42440 | Rayaneh Danesh Golestan Complex P.J.S. Co. | #23 (2) | #9 (44) | AS49666 |

| AS16322 | Parsan Lin Co. PJS | #18 (7) | #10 (42) | AS49666 |

Consolidation through the TIC certainly dominates upstream connectivity for most entities within Iran. It isn’t until twelfth place that the Institute for Research in Fundamental Sciences (AS6736) comes into play. Other AS under the same organization umbrella such as AS34837, AS35285, or AS39200 all get their upstream connectivity through the primary AS6736.

Beyond the international gateways is the realm of the NIN as it serves the internal network of Iran. Much of the intranet architecture resembles normal network designs for cloud applications. Service providers aggregate their user connectivity and funnel it toward IXPs to get the best latency to applications running in the closest datacenters. Hesam Norouz Pour has outlined a simplified typology14 of NIN:

[Internet]

|

v

[International Gateways]

|

v

[National Exchange Points]

|

v

[Edge Clouds] <------> [Data Centers / CDNs]

|

v

[Aggregation Network]

|

v

[Internet Service Provider]

|

v

[End Users]

As you can see from the simplified diagram, if Iran ever needed to shut down access to the internet it would not directly impact users ability to connect to domestic services and applications. The theory being that it would be easy to cut off the flow of international propaganda while the domestic life of citizens remained unaffected. However, this proves difficult if the actual information you are trying to stop is between citizens within the country. Group chats, message boards, and unsanctioned news articles can all freely circulate within Iran’s intranet without the need for the international internet. The Iranian government’s approach to addressing this vulnerability has been evolving along with protestors.

During the 2009 protests, the government responded simply by blocking a handful of websites and search keywords.15 Things got slightly more advanced during the 2017 protests, however, citizens were able to side step restrictions rather easily with virtual private networks (VPNs). Once protests in 2019 started up the government showed the muscles of consolidation internet connectivity and plunged the country into a week of total internet blackout, including the NIN intranet.16 Later protests in 2022 and the summer of 2025 met similar fates. Even though approximately 87% of Iranians rely on a subscription-based VPN17 it becomes rather useless during a total internet blackout.

Starlink

The introduction of Starlink satellite internet into Iran represents a fundamental shift in the struggle between digital activists and the state’s censorship apparatus. While the Iranian government has spent decades constructing a sophisticated domestic intranet to isolate its citizens during crises, the proliferation of Starlink terminals has sidestepped these digital barricades, creating a formidable challenge to state-enforced information blackouts. Imagine a simplified network topology for Iranian users:

[Internet]

|

v

[End Users]

The widespread usage of Starlink in Iran did not happen rapidly. The smuggling of hardware took years of clandestine preparation which was triggered by the violent protests of 2022.18 Following the internet shutdowns of that year, civil society groups and activists began strategizing to bypass land-based censorship infrastructure entirely. This effort was significantly aided by a 2022 U.S. government sanctions exemption, coordinated with the State Department,19 which allowed American technology companies like SpaceX to offer digital communication tools in Iran.

Encouraged by Elon Musk’s activation of the service for Iran in 2022, a complex smuggling network emerged. Activists and merchants utilized routes through neighboring countries, including the United Arab Emirates, Iraqi Kurdistan, Armenia, and Afghanistan, to sneak the hardware across the border. By early 2026, an estimated 50,000 Starlink terminals20 were operating inside the country. While initially used by human rights activists and journalists, a black market eventually developed where wealthy Iranians paid between $700 and $800 per terminal21 to access restricted platforms like Instagram and YouTube. These devices were hidden in discreet locations, such as rooftops, awaiting the next inevitable blackout.

The true strategic value of this infrastructure was tested in January 2026, when the Iranian government implemented one of the most severe internet shutdowns in its history to quell growing unrest. As land-based connections were logically severed and the country entered a digital blackout, the Starlink terminals became a critical lifeline. Unlike previous shutdowns where information flow was successfully choked off, this unfettered access to the international internet allowed images of state violence, including troops firing on protesters, to reach the outside world.22

The impact of the technology was amplified by financial intervention from SpaceX. On January 13, 2026, amid the internet blackout, SpaceX waived service fees for users in Iran.23 People could connect to the international internet simply by turning on their Starlink terminals, bypassing the hundreds of millions of dollars the Iranian government spent on building the NIN over the previous two decades. Additionally, Iranian developers devised technical workarounds to maximize the reach of the few available terminals, building tools to share connections and turn single terminals into gateways for others located farther away.24 Perhaps some sort of private network with the neighborhood Starlink terminal serving as a gateway router.

I can imagine the government’s frustration with this development. Realizing that its domestic intranet had become effectively useless, the regime escalated its response in an attempt to stop the connectivity link. They began deploying GPS jamming equipment in targeted raids, which are required for Starlink equipment to function.25 Such tactics are rarely seen outside of active battlefields like Ukraine. The raids focused its jamming efforts on neighborhoods near major universities to force students offline. Despite these aggressive countermeasures, the decentralized nature of the Starlink network has proven difficult to fully suppress. GPS jamming and radio interference could be effective in a dense urban environments but is almost impossible in the dispersed countryside.

The Iranian regime faces an escalating challenge as newer mobile devices integrate Starlink capabilities, removing the need for bulky physical terminals. The government could still interfere with Starlink operations through GPS jamming and radio interference but they’ll no longer be able to easily identify locations to action without external Starlink antennas.

The growing usage of Starlink marks a significant failure for the state’s attempt to maintain a total monopoly on information. While the penetration of Starlink shows a weakness in the NIN it does not herald the end of it. The bulk of domestic network traffic still traverses the state controlled NIN. However, it will be interesting to see at what threshold that matters if the information the government is trying to control leaks through an unregulated Starlink.

Farnaz Fassihi, Pranav Baskar, and Sanam Mahoozi, “Iran Is Cut off from Internet as Protests Calling for Regime Change Intensify,” The New York Times, January 9, 2026, https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/08/world/middleeast/iran-protests-internet-shutdown.html. ↩︎

Mehul Srivastava and Chris Campbell, “State shuts off internet but smuggled Starlink devices keep link to world,” Financial Times, January 15, 2026, p. 3. ↩︎

Hesam Norouz Pour, “The Dual Role of Iran’s National Information Network: A Primer,” European University Institute, November 2025, https://cadmus.eui.eu/server/api/core/bitstreams/1fc28765-10e6-4e6b-9335-9c260a8dea5a/content. ↩︎

Calla O’Neil, “Iran’s Digital Fortress: The Rise of the National Information Network,” American Foreign Policy Council: Iran Strategy Brief, August 2025, https://www.afpc.org/uploads/documents/Iran_Strategy_Brief_No._16_-_August_2025.pdf. ↩︎

Khosro Sayeh Isfahani, “The Internet Has No Place in Khamenei’s Vision for Iran’s Future,” Atlantic Council, July 25, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/iransource/the-internet-has-no-place-in-khameneis-vision-for-irans-future/. ↩︎

The Citizen Lab, “Iran’s National Information Network: Faster Networks, More Censorship,” The Citizen Lab, April 24, 2024, https://citizenlab.ca/irans-national-information-network/. ↩︎

Collin Anderson, “The Hidden Internet of Iran: Private Address Space on a National Scale,” arXiv:1209.6398 [cs.NI], September 28, 2012, https://arxiv.org/abs/1209.6398. ↩︎

Matthew P. Laney, “The National Information Network of Iran: A Strategic Technical and Legal Analysis” (Master’s thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, 2020), DTIC (AD1107324), December 2019, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1107324.pdf. ↩︎

Armen Shahbazian, “Analysis: The Growth of Domestic Messaging Apps in Iran,” BBC Monitoring, July 23, 2018, https://monitoring.bbc.co.uk/product/c20041be. ↩︎

Collin Anderson, “The Hidden Internet of Iran,” ↩︎

ARTICLE 19, Iran: Tightening the Net 2020: After Blood and Shutdowns (London: ARTICLE 19, September 2020), https://www.article19.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/TTN-report-2020.pdf. ↩︎

Mehul Srivastava and Chris Campbell, “State shuts off internet,” ↩︎

ARTICLE 19, Iran: Tightening the Net 2020. ↩︎

Hesam Norouz Pour, “The Dual Role of Iran’s National Information Network,” ↩︎

O’Neil, “Iran’s Digital Fortress,” 2. ↩︎

O’Neil, “Iran’s Digital Fortress,” 3. ↩︎

O’Neil, “Iran’s Digital Fortress,” 5. ↩︎

Adam Satariano, Paul Mozur, and Sheera Frenkel. “How Activists in Iran Are Using Starlink to Stay Online.” The New York Times, January 16, 2026. https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/15/technology/iran-online-starlink.html?campaign_id=2&emc=edit_th_20260116&instance_id=169402&nl=today%27s-headlines®i_id=69207950&segment_id=213781&user_id=8eca66a41bad4639d6a80be52119fbd8. ↩︎

Satariano, “How Activists in Iran Are Using Starlink” ↩︎

Satariano, “How Activists in Iran Are Using Starlink” ↩︎

Satariano, “How Activists in Iran Are Using Starlink” ↩︎

Satariano, “How Activists in Iran Are Using Starlink” ↩︎

Natallie Rocha, “Starlink Users in Iran Get Free Internet Access, Nonprofits Say,” The New York Times, January 14, 2026, https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/13/technology/iran-starlink-elon-musk.html. ↩︎

Satariano, “How Activists in Iran Are Using Starlink” ↩︎

Satariano, “How Activists in Iran Are Using Starlink” ↩︎

⁂