Chrome Featured Extension Is Actually A Scraper Network

Update on January 30, 2026: A MyBib developer contacted me about this extension’s behavior. They confirmed that this was expected behavior and it was how they were pooling the retrieval of user citation requests. The instance where my computer downloaded several PDF files was a bug that has since been fixed. MyBib has updated the language in the Chrome Web Store to reflect the reality of what the extension was doing in the background.

Note: In order to keep MyBib free, the MyBib extension may, from time to time, utilize unused bandwidth to crowdsource the collection of citation data for everyone citing on MyBib. This is anonymous and only occurs when your browser is not being used.

tl;dr Popular Chrome extension MyBib uses your computer to scrape random educational websites.

I was downloading some files a few weeks ago and noticed something strange. I didn’t recognize two PDF files in my Downloads folder. They had the timestamp of 4:23 a.m. and 3:05 a.m. Uh, what the hell? Like any good security technologist I raw dogged those files and opened them up to see what they were. The first was “The Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC): Challenges for the Islamic World” by Dr. Ghulam Mustafa and Nusrat Bano. Not exactly in my area of interest in Political Science but perhaps I downloaded them unintentionally. Maybe I was clicking around too fast on some random site.

The second file was a master’s thesis from Fantahun Ali Amedie, titled “Impacts of Climate Change on Plant Growth, Ecosystem Services, Biodiversity, and Potential Adaptation Measure.” I’m not really an atmospheric science person so this being on my computer made a lot less sense. Also, the early morning retrieval time alarmed me. I asked my wife jokingly if she was doing some late night research on my computer while I was sleeping.

I reviewed my Chrome history and sure enough there were the entries at the right times. Somehow my Chrome was going to websites when I wasn’t around. But looking closer there were even more requests all through the night! Uh, what the hell? All of them went to this domain called ResearchGate. Who were these bastards and what had they done to my computer? I looked them up. While commercial, they were at least legitimate. They were an aspiring social networking site for scientists and researchers.1

My paranoia was in a weird state at this point. Initially, I assumed this errant traffic was limited to browsing random academic studies. It was odd but not a serious emergency. Like almost as if a script kiddie that only wore tweed jackets with elbow patches had taken over a portion of my computer.

But my paranoia kept solidifying. I had recently witnessed a close family friend rebuild their digital life after a SIM swap attack. This person had spent weeks reestablishing themselves back into the modern world. It wasn’t something I wanted to live through and had spent the past weekend updating old passwords, adding two factor authentication where missing, and generally securing things.

I took to Google, though I stalled when phrasing the search. It wasn’t as if my computer was going to random websites you’d normally associate with malware. My computer was in its academic arc and was obsessed with ResearchGate. I typed in computer going to researchgate randomly. I got results for how to add an article on ResearchGate. Not very helpful. I pulled back a little broader and tried computer going to random sites. Yes, potentially malware but why only this academic ResearchGate site?

While I had Malwarebytes doing a scan I kept searching through Reddit and forum posts. Many of the conclusions were that certain Chrome extensions could be responsible for such erratic behavior. But I had only six extensions and most were either Chrome Featured or had millions of users.

The Malwarebytes scan returned zero results. My only remaining option was to scorch the earth and restore Chrome to its default settings. I deleted all six of my installed extensions and sanitized other custom settings. The only way to tell if anything worked was to wait a few days to see if random browsing was still taking place. Luckily, this happened over the holidays and I had plenty of time.

After a week there was no new late night activity. Such a relief! It felt like my house’s front door finally had a lock on it again. I had broadly isolated the cause to a random extension I was using. I re-added three extensions, choosing them purely by the number of users. One had as few as 3,000. This approach might seem arbitrary, but sketchy behavior would likely evade detection more easily on a less popular extension.

I waited another week and nothing happened. Then I realized the academic nature of the random browsing provided the biggest clue. Out of the remaining 3 extensions I had yet to test, two were citation generators, Scribbr and MyBib. Yes, I realize I’m a lazy bastard for using such extensions but it takes the busy work out of writing a citation. I’m a firm believer that citations are massively superior to hyperlinks, as you can see on any past articles on this blog. They maintain an adequate amount of information needed to look up a source in the inevitable case that a hyperlink URL rots away.

I re-installed Scribbr and waited. A week later nothing had happened. So I moved on to MyBib. A few hours after re-installing it I noticed out of the corner of my eye a new tab pop up and then rapidly disappear. Uh, what the hell? In my Chrome history it showed I had just gone to another ResearchGate study. Ok, I found the source but I wanted to explore what exactly was happening.

I’m a network engineer by trade so my automatic reaction to most problems is a packet capture. This often isn’t very efficient because packet captures are overly verbose and require a great deal of refinement to reach what you are actually interested in finding. And after looking through Wireshark there was another problem, encrypted traffic. This exposed my lack of familiarity with Session Key Logging on macOS where you essentially dump the encryption keys Chrome is using to talk with the far end domain. You can then use this to decrypt the traffic. Perhaps there was something further up the OSI stack that I could use to find what I needed faster.

A quick Google search gave me a hint. If I enabled Developer mode on the Chrome extension page it would allow me to view each extension’s service worker and all the operations it was performing. Clicking on the service worker of an extension essentially opens a DevTools page that shows all the normal diagnostic tabs like sources, network, performance, memory, and application. So I opened the network tab and waited.

After a few hours I came back to a few results. I discovered that these sites were not exclusively ResearchGate. There were many other sites but only ResearchGate was showing up in my Chrome’s browsing history. What were these ghost requests? I could see that the extension was reaching out to them but the only record of them ever taking place was in this DevTools page. The frequency wasn’t blistering but still semi-frequent. All without my intervention.

Under the Initiator tab on a particular GET request I could see a script referenced: service_worker.js:1. I’m not well versed with coding and even less so with JavaScript so I asked my wife to help look at this script. Our goal was to find the part that had instructions for my computer to go to these random sites.

The code excerpt below stood out as the basis of how this particular extension was sending instructions to my computer through a WebSocket connection.

(n = new WebSocket(`wss://ws.mybib.com/?v=${t}`)).onopen = function() {

console.log(">");

const e = setInterval(( () => {

n && 1 === n.readyState ? n.send("// stay alive") : clearInterval(e)

}

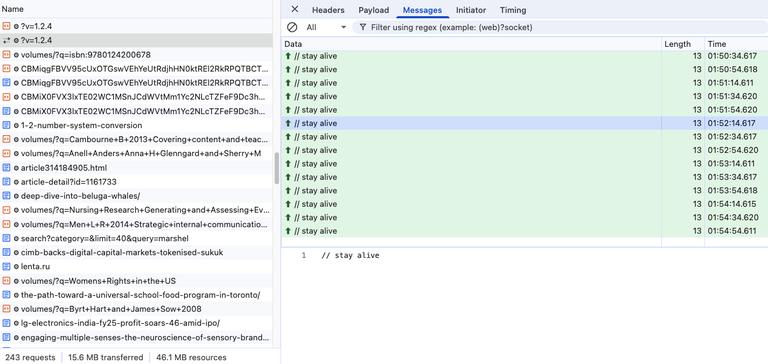

I looked for traffic to this particular domain in the DevTools Network page. And sure enough, there was a live WebSocket connection to wss://ws.mybib.com/?v=1.2.4. Under it I could see these //stay alive messages going along at a quick 20 second interval.

These keep alive messages appear to force my computer to check in with the MyBib servers and await instructions. They were only interrupted by random scrape instructions. Please, obedient zombie computer, issue a GET request to this particular URL and tell us what you find.

{

"headers": {

"Cache-Control": "no-cache"

},

"id": "cace6dfb5f7f46f0a7bd4f02c217eb1f",

"url": "https://blog.reworld.eco/afforestation-vs-reforestation-whats-the-difference-and-why-do-they-matter-46730cbce304",

"method": "GET",

"data": "",

"useTab": false,

"listenForRequestUrl": null,

"listenForRequestContentString": null

}

And then a few minutes later my computer would respond with the scrape request. Notice how the id field matches. I assume this is how the MyBib server keeps track of multiple scrape requests. Please note I abbreviated the output. It was the entire HTML of the page. The real point I wanted to make with this output was the id and useTab parameters.

{

"id": "cace6dfb5f7f46f0a7bd4f02c217eb1f",

"response": {

"data": "<!doctype html><html lang=\"en\"><head><title data-rh=\"true\">Afforestation vs Reforestation: What’s the Difference and Why Do They Matter? | by Matthew Wheatley | ReWorld</title>

...

...

"withCredentials": true,

"id": "cace6dfb5f7f46f0a7bd4f02c217eb1f",

"url": "https://blog.reworld.eco/afforestation-vs-reforestation-whats-the-difference-and-why-do-they-matter-46730cbce304",

"method": "get",

"data": null,

"useTab": false,

"listenForRequestUrl": null,

"listenForRequestContentString": null

},

"request": {}

}

}

Here is another scrape request from MyBib:

{

"headers": {

"Cache-Control": "no-cache"

},

"id": "4a6398b5aa304e5a9e5f7b8722a5398f",

"url": "https://www.lonelyplanet.com/turkey/aegean-coast/pamukkale/attractions/necropolis/a/poi-sig/1262860/360866",

"method": "GET",

"data": "",

"useTab": false,

"listenForRequestUrl": null,

"listenForRequestContentString": null

}

And my abbreviated computer’s reply with the same id.

{

"id": "4a6398b5aa304e5a9e5f7b8722a5398f",

"response": {

"data": "<!DOCTYPE html><html><head><meta charSet=\"utf-8\"/><meta name=\"viewport\" content=\"width=device-width, initial-scale=1\"/><meta property=\"fb:app_id\" content=\"111537044496\"/><meta property=\"og:site_name\" content=\"Lonely Planet\"

...

...

"withCredentials": true,

"id": "4a6398b5aa304e5a9e5f7b8722a5398f",

"url": "https://www.lonelyplanet.com/turkey/aegean-coast/pamukkale/attractions/necropolis/a/poi-sig/1262860/360866",

"method": "get",

"data": null,

"useTab": false,

"listenForRequestUrl": null,

"listenForRequestContentString": null

},

"request": {}

}

}

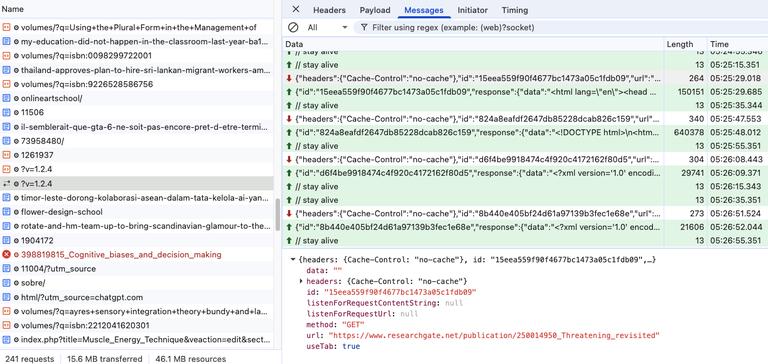

Surprisingly, the behavior of opening ghost tabs in Chrome was rather rare for MyBib. It took me almost half a day of watching to see a request and to match that up to my Chrome browsing history. It appears this is needed due to some strict websites that enforce particular user agents or other technical limitations of the previously shared headless GET requests. Below is an example with useTab set to true:

{

"headers": {

"Cache-Control": "no-cache"

},

"id": "15eea559f90f4677bc1473a05c1fdb09",

"url": "https://www.researchgate.net/publication/250014950_Threatening_revisited",

"method": "GET",

"data": "",

"useTab": true,

"listenForRequestUrl": null,

"listenForRequestContentString": null

}

And then my abbreviated computer’s reply:

{

"id": "15eea559f90f4677bc1473a05c1fdb09",

"response": {

"data": "<html lang=\"en\"><head prefix=\"og: http://ogp.me/ns#\">\n <meta charset=\"utf-8\">\n <meta http-equiv=\"content-type\" content=\"text/html; charset=UTF-8\">\n <meta name=\"referrer\" content=\"origin-when-cross-origin\">\n

...

...

<title>(PDF) Threatening Revisited</title>\n<meta name=\"description\" content=\"PDF | This paper considers the act of verbal threatening. I first examine what constitutes a verbal threat, concluding that it involves conveying both</div></body></html>",

"status": 200

}

}

We were able to identify the instructions for this behavior in the service worker JavaScript file. If useTab was set to true it would perform some shady behavior:

r.useTab)

chrome.tabs.create({

active: !1,

pinned: !0,

url: r.url

}, (function(e) {

When active was specified as !1 it would prevent your Chrome window from becoming the front and center when the page request was processing. Certainly to avoid attracting the attention of users that might be currently working on the computer. The pinned specification of !0 makes a pinned tab, which is overall smaller in the top menu and further obfuscates the visual representation of the process if a user was actively paying attention.

I was able to replicate this extension’s behavior across different platforms. My own computer is running MacOS Sequoia 15.7.2 with Google Chrome version 143.0.7499.170. I also encountered the same scraping behavior on another computer I have that is running Windows 10 Pro (OS build 19045.5737) with Google Chrome version 143.0.7499.193. Both systems were running version 1.2.4 of the MyBib extension.

I’m honestly flabbergasted this extension is behaving this way. I never signed up to be part of a distributed scraper network meant to evade the rate limiting security measures of websites. The audacity to hijack your user’s computer is profoundly arrogant. Even for a free extension there are certain expectations around how things should behave in the realm of security. Or at the very least, some sort of communicated disclaimers around the realm of security. Maybe that is just my own flawed reasoning, which will undoubtedly be further jaded after this encounter?

I could understand the need for this on-demand scraping capability if you wanted to spread the compute load around. Take the fictional scenario where someone develops an extension but wants to keep it free, avoid subscriptions, and keep infrastructure costs low. This might require moving some of the compute burden onto the users. Instead of paying for widely distributed infrastructure you could instead just assign out the scraping task to a user who has your extension installed. A simple minor trade wherein the user pays with some compute for access to the free extension.

I could see this exchange playing out just fine in the modern world. All you’d need is a few sentences on your extension page saying this was the terms of exchange. Users could then expect to see scraping activity and know it was their paid cost to using the extension. However, this is not the case. There is absolutely no mention of this behavior on the MyBib extension page, which has over 1,000,000 Chrome users, their terms of service, or privacy policy pages.

MyBib’s actions don’t take place in a vacuum. They are a Featured extension in the Google Chrome Web Store. Google’s definition of this is kind of vague but should supposedly instill some level of confidence in whatever extension you are installing.

Featured extensions follow our technical best practices and meet a high standard of user experience and design. Chrome Web Store Help

Google’s evaluation criteria obviously need rework if an extension like this can evade detection. Or alternatively, provide some mechanism for some sort of annual audit to make sure underlying functionality hasn’t become malicious with a new update. Furthermore, this might have some implications for Google’s Advanced Protection Program, which I have opted into. Google says it performs even more stringent malware checks for Google Chrome but this extension was operating just fine.

To be fair to Google and MyBib, this extension’s behavior isn’t specifically malicious. From what I have seen it is a distributed educational website scraper. Not something I want operating on my computer but definitely better than a million other sketchy applications. My bank account is intact and my digital life hasn’t been disturbed. But in the end, since MyBib was never forthright about their extension’s behavior, it is unforgivable.

Katie Fortney and Justin Gonder, “A Social Networking Site Is Not an Open Access Repository - Office of Scholarly Communication,” University of California, December 1, 2015, https://osc.universityofcalifornia.edu/2015/12/a-social-networking-site-is-not-an-open-access-repository/. ↩︎

⁂