Mine, All Mine

I stepped into a music store this weekend for the first time in quite a while. I was compelled by an urge to possess something tangible. It was a strange feeling because the phone in my pocket was capable of instantly streaming probably a vast majority of the music in the store. But access to something doesn’t mean you own it.

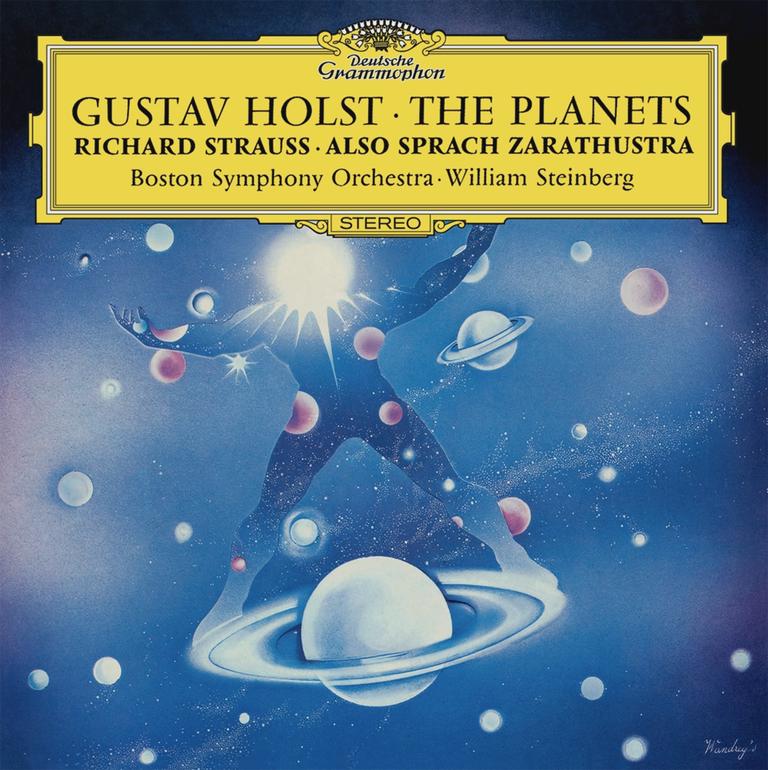

Flipping through boxes of new and vintage vinyl came with sticker shock. A hefty $29.99 for a re-pressed vinyl record was a stretch from my $11.61 a month Qobuz subscription. There were even deluxe edition albums for even more at $59.99. The ever-present subscription business model has programmed this immediate comparison into me over the past decade. We no longer own things but instead pay a monthly fee for access. But recently, I have been trying to understand this relationship with a bit more nuance than just raw dollars and what ownership means to me personally.

A music, movie, or television show streaming service isn’t very useful when the internet is out. You can cache music for offline listening but let’s ignore the corner cases for now and just approach the topic in general terms. Media access also exists at the whims of licensing deals that come and go. A movie or television show on Netflix one week might not be there the next. Will you need a new subscription to Netflix or Hulu in order to keep watching your favorite show? This isn’t as apparent for music streaming services, seeing as Qobuz offers over 100 million songs,1 on par with Spotify.2 But there are still issues with some artists3 not being on a certain platform that could be a problem for some.

The overall cohesiveness for music streaming services is great but falls apart when you start thinking about movies or television shows. In today’s vast variety of streaming services you’ll have to look up your show to see where it’s available,4 if anywhere. After you sign up for that service there is also no guarantee that it will remain there. I have experienced two instances of being in the middle of watching a television show, only to have it disappear from the service to which I was subscribed. I’m picturing a representative of a major studio showing up at my house, plucking a DVD from my collection and leaving with it.

Is physical media ownership the answer to these dilemmas? I think so, at least in several aspects. After I purchase a Blu-ray or CD it marks the end of my relationship with the seller and I keep the media forever. The state of that media is then fully static. However, with streaming, that transaction is perpetually extended. Over the course of the streaming relationship I can lose access to specific media based on the decisions of the streaming service. A slightly weirder case is when the director or studio releases subsequent editions5 that don’t exactly match what was originally shown in theaters.

I realize none of these concepts are new but they seem to have faded into the background of my mind over the past decade with the growing use of subscription-based models. The convenience lulls me into a passive state of mind and I completely forget about it. But then these huge AWS outages happen that break the things I own6 and I’m left facing the reality that I immensely depend on these external services for the majority of my things to work. Should it be that way and to what degree am I comfortable? In this thought process I ask myself what it would take to partially remove my dependency on these services.

I’ll admit, it isn’t feasible to build your own personal music collection of 100 million songs so my music streaming service will have to stay. Qobuz has been doing a tremendous job helping my discovery of new music over the past few years. Real people curate new album releases every week. This meatspace curation hasn’t gone unnoticed; as Andrew Dubber notes, “Qobuz assumes I’m interesting, Spotify assumes I am predictable.”7 It has helped me discover standout albums like Fat Dog’s WOOF and 100 gecs’ 10,000 gecs that might not have reached me through Spotify’s algorithm. From this path of discovery I can curate a list of albums that I can reference when I’m at the music store. I’ll approach using a music streaming service like an easy-access sampler to see if I like something before I make a larger investment in a physical copy for my own collection.

For movies and television shows, which are less aggregated, it would be more beneficial for me to lean harder on owning and purchasing physical copies rather than subscribing to an inordinate amount of streaming services. There is also another problem where some movies aren’t even available on any streaming services.8 Shows coming out of the HBO studio seem to align with my tastes most consistently with Apple in a close second. But everything after that is kind of hit or miss and largely depends on the show itself. Considering the instability of availability for these types of media it would be really nice to have physical copies for my own collection. And the overall amount required for a decent library isn’t nearly as much as in the realm of music.

The novel idea of ownership is probably obvious to many people in this age of streaming but for me it had been an idea that had faded away over the past few years. Purchasing a video game on Steam and downloading it in minutes without having to trudge down to the local game store is purely awesome. I pay for that convenience by forfeiting ownership of my Steam games9 and other things like Kindle books.10 The tradeoff of this convenience might be too much for some and perfectly fine for others. I’m going to approach the whole situation pragmatically, accepting that convenience sometimes comes at the cost of ownership.

“The Qobuz Experience,” Qobuz Help Center, accessed November 17, 2025, https://help.qobuz.com/en/articles/10127-the-qobuz-experience. ↩︎

Will Howard, “How Many Songs Are There on Spotify?,” Far Out Magazine, November 17, 2024, https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/how-many-songs-are-there-on-spotify/. ↩︎

Ben Sisario, “Joni Mitchell Plans to Follow Neil Young off Spotify, Citing ‘Lies,’” The New York Times, January 30, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/28/arts/music/joni-mitchell-neil-young-spotify.html. ↩︎

See “JustWatch,” accessed November 17, 2025, https://www.justwatch.com/us; “Reelgood,” accessed November 17, 2025, https://reelgood.com/. ↩︎

“Changes in Star Wars Re-releases,” Wikipedia, accessed November 17, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Changes_in_Star_Wars_re-releases. ↩︎

Sopan Deb, “AWS Cloud-Computing Outage Left Smart Bed Customers Without Sleep,” The New York Times, October 24, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/10/24/business/amazon-aws-outage-eight-sleep-mattress.html. ↩︎

Andrew Dubber, “Music Discovery: Qobuz Vs Spotify,” MTF Labs, July 6, 2023, https://andrewdubber.com/music-discovery-qobuz-vs-spotify/. ↩︎

Wilson Chapman, “The 30 Best Movies Currently Not Streaming Anywhere: ‘Short Cuts,’ ‘Pink Flamingos,’ ‘Cocoon,’ and More,” IndieWire, July 8, 2025, https://www.indiewire.com/gallery/best-films-unavailable-streaming/blonde-venus-from-left-sidney-blackmer-marlene-dietrich-1932/. ↩︎

Kyle Barr, “Steam Finally Makes It Clear You Don’t Own Your Games,” Gizmodo, October 11, 2024, https://gizmodo.com/steam-finally-makes-it-clear-you-dont-own-your-games-2000511155. ↩︎

Joel Johnson, “You Don’t Own Your Kindle Books, Amazon Reminds Customer,” NBC News, October 24, 2012, https://www.nbcnews.com/technolog/you-dont-own-your-kindle-books-amazon-reminds-customer-1c6626211. ↩︎

⁂