Would China Target Taiwan’s Submarine Internet Cables During Invasion?

The seemingly ever present threat of China invading Taiwan stands as one of the most critical and closely watched geopolitical flashpoints globally. Decades of political separation between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan, coupled with Beijing’s unwavering claim of sovereignty over the island and its refusal to renounce the use of force, creates an undying risk of conflict.1 This risk is amplified by the PRC’s extensive military modernization program, which has been significantly driven by the objective of developing capabilities to compel unification with Taiwan, potentially through coercion or outright invasion.2

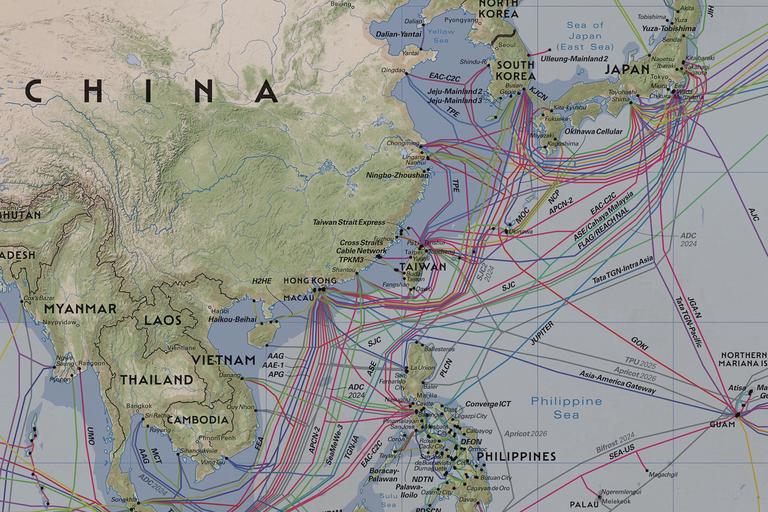

Among the most vital components of modern global infrastructure are submarine communication cables. These undersea fiber optic networks serve as the backbone of the internet and international communications, carrying an estimated 95 to 99 percent of all intercontinental data traffic.3 They facilitate trillions of dollars in financial transactions daily4 and are essential for global commerce, scientific collaboration, government operations, and military command and control.5 Despite their criticality, these cables are inherently vulnerable due to their physical fragility and unguarded presence. They lie exposed on the seabed floor and can be damaged from natural events or accidental or even intentional human activities. The worst part of all is that they often converge at a limited number of terrestrial landing stations in a choke point that creates a lucrative target during any conflict. Balancing this extreme importance and physical vulnerability places submarine cable security at the center of strategic considerations in potential conflict scenarios, particularly those involving highly digitized economies and potential maritime battlegrounds like the Taiwan Strait. The reliance is not merely economic. Military and governmental communications heavily depend on these commercial networks.6

Based on the criticality of Taiwan’s submarine internet cables how likely is it that the PRC would deliberately target and sever Taiwan’s submarine internet cables during a potential invasion or blockade scenario? One key way of answering this hypothetical is attempting to understand Beijing’s strategic calculus, including PLA doctrine regarding information warfare and critical infrastructure attacks. Additionally, what are the technical capabilities of the PLA Navy for undersea operations when compared to Taiwan’s specific vulnerabilities and resiliency measures?

Understanding the potential for PRC to target Taiwan’s submarine communication cables requires an attempt to understand the doctrinal foundations of the PLA’s approach to modern warfare, specifically for information dominance and operations against critical infrastructure. The Taiwan scenario remains the “primary driver”2 for PLA modernization efforts and its principal contingency focus, shaping force development, training, and strategic thought for decades. Statements by Xi Jinping have consistently underscored the military dimensions of the Taiwan issue, reinforcing the PLA’s mandate to prepare for coercion or forceful reunification.2

Central to the PLA’s contemporary warfighting philosophy is the concept of “information warfare” (信息化战争, Xìnxī huà zhànzhēng) and “systems confrontation” (体系对抗, Tǐxì duìkàng).7 These concepts were formed and heavily influenced by observations of U.S. military operations since the 1991 Gulf War. Subsequently, the PLA has shifted focus from traditional attrition warfare aimed at annihilating enemy forces to a strategy centered on disrupting, paralyzing, or destroying the adversary’s entire operational system.7 Information Warfare emphasizes that information dominance is a prerequisite for success across all domains including land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace.7 Victory through informational warfare is achieved not just by destroying material means, but by disrupting the adversary’s ability to acquire, transmit, process, and utilize information effectively. Influential PLA texts like the 2020 Science of Military Strategy assert that winning information warfare is the “fundamental function”8 of the military and that all modern warfare is essentially information warfare. The method for achieving victory in this context is termed “system destruction warfare” (体系破击战, Tǐxì pò jí zhàn), which involves targeting critical nodes and functions within the enemy’s operational system to induce paralysis or collapse.9

Within this warfare framework, the PLA has developed specific campaign concepts relevant to a Taiwanese scenario, most notably the “joint blockade campaign” (联合封锁战役, Liánhé fēngsuǒ zhànyì).10 Described in authoritative sources like the 2006 PLA National Defense University’s Science of Campaigns, this concept envisions a large-scale, potentially long-term operation aimed at isolating Taiwan by asserting air, maritime, and information dominance.11 Crucially, this campaign explicitly includes not only traditional blockade actions like intercepting ships and aircraft, but also firepower strikes against key facilities like ports or airfields, mining maritime approaches, and conducting both kinetic and non-kinetic attacks on information systems and infrastructure.11 Such a blockade could serve as a coercive measure short of actual invasion, a preparatory phase for an amphibious landing, or a primary means to achieve victory by strangling Taiwan into submission.11

The PLA’s doctrinal emphasis on information dominance and system disruption directly implies the targeting of communication infrastructure. PLA writings explicitly mention targeting long-haul communications facilities, including satellite ground stations and undersea cable landing sites, as part of the initial strikes in a blockade scenario aimed at severing Taiwan’s external communications.11 Beyond these explicit mentions, the broader concepts of “systems destruction warfare” and “information warfare” inherently encompass critical communication nodes like submarine cables. Targeting these cables aligns with the doctrinal goals of degrading information flow within Taiwan’s information system architecture.7

All of the PLA’s doctrinal proclamations clearly indicate a specific approach towards prioritizing the disruption of an adversary’s information systems as a central element of modern warfare. Concepts like “information warfare" and “systems destruction,” particularly when applied within the framework of a “joint blockade campaign” against Taiwan, strongly suggest that critical communication infrastructure, including submarine internet cables, are considered legitimate and important targets. This doctrinal emphasis points to consider attacks on Taiwan’s vital communication links as extremely likely, and perhaps an essential component of any future conflict scenario.

China possesses or is developing sophisticated technologies for undersea operations relevant to cable disruption. Research conducted at institutions with strong defense ties, such as Harbin Engineering University and the Ocean University of China, has focused on enhancing the ability to locate undersea cables, even those buried beneath the seabed. Methods include algorithmically enhanced robotics employing novel magnetic induction techniques and advanced sonar systems combining multiple technologies for improved detection and navigation to fault sites.12 While often framed for civilian applications like infrastructure maintenance or offshore wind farm support, these localization technologies have clear dual-use potential for military purposes, including identifying cables for surveillance or sabotage.12

On a more basic approach, China has demonstrated capabilities for cutting submarine internet cables. Patents filed by PLA affiliated bodies, such as the PLA Navy Institute of Communication Application and the PLA Naval University of Engineering, explicitly describe devices for shearing deep sea optical cables and retrieving them, strongly suggesting military intent for sabotage or tapping.12 Civilian institutions and companies, like Lishui University and Zhuhai Yunzhou Intelligence Technology, have also patented towed or deployable cutting devices, purportedly for emergency repairs or salvage but readily adaptable for military or gray zone use.12 Recent reports highlight the development of a deep sea tool, potentially ship deployed, capable of cutting heavily fortified cables at depths up to 4,000 meters.4 While the necessity for such extreme depth and cutting power against typical unarmored deep-sea cables is questionable,13 the capability itself represents a significant advancement. Specialized surface vessels such as research ships or cable layers and potentially subsurface platforms like submarines (similar to Russia’s AS-31 Losharik14) or unmanned underwater vehicles12 could be employed to deploy these infrastructure interference tools.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence of China’s capability and potential willingness to interfere with undersea cables comes from numerous documented incidents in recent years, particularly because they employ “gray zone” tactics. These involve actions below the threshold of armed conflict, often designed to be ambiguous and deniable.3 Multiple incidents near Taiwan have been attributed by Taiwanese authorities to Chinese fishing boats or cargo ships. These specifically include the severing of both cables connecting the Matsu Islands on February 12, 2023 3 and subsequent incidents near Taiwan proper with cables off the coast of Penghu15 and Keelung.16 Similar incidents in the Baltic Sea, involving C-Lion1 and BCS East-West Interlink cables, have also implicated Chinese-flagged or associated vessels, sometimes operating out of Russian ports.15

These incidents often involve methods that mimic common accidents, such as anchors being dragged across cables.15 The use of civilian vessels, sometimes operating under flags of convenience or engaging in identity tampering including manipulating AIS transmissions or using multiple identities,15 provides a crucial layer of plausible deniability.3 While definitive proof of state direction is often elusive, the pattern, frequency, location proximity to sensitive areas and critical infrastructure, and alignment with China’s broader strategic interests strongly suggest intentionality in many cases.15

This pattern of repeated, deniable disruptions serves multiple purposes. It allows China to test adversary responses, probe vulnerabilities in detection and repair capabilities, exert psychological pressure, and potentially normalize such incidents as mere accidents.3 By demonstrating the capability and willingness to interfere with critical infrastructure in peacetime or low-level crises, China may be lowering the perceived threshold for employing similar scaled-up tactics during a future conflict while aiming to maintain ambiguity and control escalation.

Taiwan’s position as a modern, technologically advanced democracy and a linchpin in global supply chains is inextricably linked to its robust digital connectivity. This connectivity, however, relies overwhelmingly on a network of international submarine communication cables, creating significant strategic dependencies and vulnerabilities that could be exploited in a conflict scenario.

Taiwan is connected to the global internet primarily through 15 international submarine internet cables.3 This infrastructure provider over 100 Tbps of bandwidth to 21.71 million Taiwanese making it one of the world’s highest internet penetration rates.17 This raw capability underpins virtually all aspects in critical industries like semiconductor manufacturing, financial services, government functions, military command and control, and daily civilian life.3 The heavy reliance on a relatively small number of physical conduits creates a fundamental dependence on all mentioned sectors and any significant disruption to these cables could severely isolate the island digitally.18

Compounding this dependence is the geographic concentration of Taiwan’s cable infrastructure. Most of the submarine internet cables land in just three main areas: Toucheng in the northeast, Fangshan in the south, and the New Taipei/Tanshui area in the north.3 This limited number of cable landing stations (CLS) creates critical choke points. A RAND study assessed that a successful attack on either the Toucheng or Fangshan landing sites could have a “sudden and calamitous effect” on Taiwan’s external communications.19 Furthermore, analysis suggests that at least one CLS in Tanshui has been specifically identified as a point of interest tracked by a China affiliated entity, indicating potential hostile reconnaissance targeting these vulnerabilities.20

The economic stakes associated with Taiwan’s connectivity are immense, both domestically and globally. A disruption of Taiwan’s submarine cables would paralyze its digital economy, estimated to reach NT$6.5 trillion (USD $204 billion) by 2025.21 Financial markets would be severely impacted, as demonstrated by slowdowns during the 2006 earthquake and disruptions to online banking seen during the Matsu cable cuts.3 Interruptions could cost millions per hour.22

Crucially, Taiwan plays an indispensable role in the global semiconductor supply chain, producing the vast majority of the world’s most advanced logic chips and a significant share of chips for automotive and consumer electronics.23 A blockade or conflict that severs Taiwan’s connectivity would halt this production and export, triggering catastrophic disruptions across numerous downstream industries worldwide, including electronics, automotive, computing, telecommunications, and medical devices.23 Economic modeling by institutions like the Rhodium Group, Bloomberg Economics, RAND, and the St. Louis Federal Reserve consistently projects global economic losses in the trillions of dollars from a Taiwan conflict scenario, largely driven by the interruption of the semiconductor supply chain reliant on Taiwan.24 The Rhodium Group conservatively estimated that companies dependent on Taiwanese chips could lose $1.6 trillion in annual revenue during a blockade.25 This highlights that targeting Taiwan’s cables is not just an attack on Taiwan itself, but potentially a potent form of global economic coercion. China could leverage the threat or act of cutting Taiwan’s cables to inflict widespread economic pain, potentially aiming to deter international intervention or sow discord among nations dependent on Taiwan’s technological outputs.1

Severing Taiwan’s international communication links would have huge military implications. It would directly impede Taiwan’s ability to communicate and coordinate with external partners, primarily the United States, potentially delaying or complicating any international response or intervention efforts.3 Active intelligence sharing and coordinated military actions rely heavily on secure, high-bandwidth communications, which are predominantly carried by commercial submarine internet cables.6 Disrupting these links would force reliance on alternative systems like satellite communications, which offer significantly lower bandwidth and latency, may be more susceptible to jamming or kinetic attack, and could compromise operational security if forced onto less secure channels.26 Isolating Taiwan digitally could also degrade its own military’s situational awareness, which would hinder its ability to mount a cohesive defense.27 Furthermore, cutting external communication lines could create an environment ripe for psychological operations and disinformation campaigns, as Taiwan’s population and leadership would struggle to verify information or counter PLA propaganda effectively.3

Despite the potential military utility, attacking international submarine cables entails enormous risks for China. The primary deterrent is the potentially catastrophic global economic fallout.1 Given Taiwan’s critical role in global supply chains, particularly semiconductors, severing its links would likely trigger a global recession, severely damage China’s own economy, which relies heavily on international trade, and invite crippling international sanctions.1 Diplomatic consequences would likely include widespread condemnation, further isolation, and the potential formation of broad international coalitions aimed at constraining China’s power.28

Perhaps even more important, attacking internationally owned infrastructure carries a high risk of escalation.6 Such actions could be interpreted as a direct attack on other nation state interests, potentially solidifying political will in Washington and allied capitals for direct military intervention or intensifying an ongoing intervention.2 China’s leaders are likely aware that crossing this threshold could lead to a wider, more protracted, and potentially uncontrollable conflict with the United States, undermining their strategic objectives.28

However, some reviews suggest that if Beijing were to decide to initiate an invasion or full blockade, it would have already calculated and accepted enormous sunk cost that would include significant economic damage and becoming an international pariah.11 Where catastrophic consequences are already anticipated, the marginal cost of adding cable cutting to the list of hostile actions might appear incredibly minor in Beijing’s calculus.11 The perceived military necessity of isolating Taiwan quickly to achieve decisive victory before effective intervention could occur might override concerns about additional economic or diplomatic fallout.29 The effectiveness of economic costs as a primary deterrent could be easily debatable. While generally significant,28 their marginal impact might decrease once a high-intensity conflict is already underway.30 China’s ultimate decision would likely depend on its assessment of the specific circumstances, its risk tolerance, and its confidence in achieving its primary objectives swiftly.29 The potential for the conflict itself to cause such severe economic disruption that formal sanctions become somewhat ineffective is a factor that could paradoxically lower the threshold for cable attacks within an already escalated conflict, even as the overall economic consequences act as a deterrent against initiating the conflict in the first place.30

Considering these competing factors, the likelihood of China launching widespread, easily attributable attacks against Taiwan’s international submarine cables appears conditional and likely not a preferred opening move. While doctrinally sound from a PLA perspective and technically feasible, the immense potential for global economic disruption, severe diplomatic backlash, and uncontrollable military escalation makes it an extremely high-risk option. Such actions seem more plausible under more strained conditions if China felt bogged down in a protracted conflict and its initial objectives were failing. Alternatively, if China believes it can achieve a rapid victory before repercussions materialize it could be worth the plethora of costs with attacking submarine internet cables. The decision is heavily contingent on Beijing’s real-time assessment of the strategic environment, particularly the perceived resolve and appetite of the U.S. to intervene effectively.1

However, the likelihood of selective targeting or the use of deniable, gray zone style disruptions appears considerably higher. China might prioritize targeting specific cables deemed less critical to major powers or focus attacks on landing stations within Taiwan’s territory, framing it as part of the direct assault on Taiwan rather than an attack on international infrastructure.11 Employing tactics similar to those seen in the Matsu and Baltic incidents, using civilian vessels under ambiguous circumstances to cause “accidental” damage, remains a plausible scenario, especially in the lead-up to or early stages of a crisis, as it offers disruption while attempting to manage escalation and maintain deniability.3

Kevin Rudd, “The United States, China and Taiwan and the Role of Deterrence in Scenarios Short of War” (speech, Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, Honolulu, Hawaii, June 6, 2024), https://usa.embassy.gov.au/APCSS24. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Joel Wuthnow, “System Overload: Can China’s Military Be Distracted in a War over Taiwan?," China Strategic Perspectives, No. 15, June 2020, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratperspective/china/china-perspectives-15.pdf. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Fern Hinrix, “Building Resilience in Taiwan’s Internet Infrastructure From Geopolitical Threats," The Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies,” May 21, 2024, https://jsis.washington.edu/news/building-resilience-in-taiwans-internet-infrastructure-from-geopolitical-threats/. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Erin Murphy and Matt Pearl, “China’s Underwater Power Play: The PRC’s New Subsea Cable-Cutting Ship Spooks International Security Experts,” Center for Strategic & International Studies, April 4, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-underwater-power-play-prcs-new-subsea-cable-cutting-ship-spooks-international. ↩︎ ↩︎

Madison Long, “Information Warfare in the Depths: An Analysis of Global Undersea Cable Networks,” U.S. Naval Institute, May 31, 2023, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2023/may/information-warfare-depths-analysis-global-undersea-cable-networks. ↩︎

Colin Wall and Pierre Morcos, “Invisible and Vital: Undersea Cables and Transatlantic Security,” Center for Strategic & International Studies, June 11, 2021, https://www.csis.org/analysis/invisible-and-vital-undersea-cables-and-transatlantic-security. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

B. A. Friedman, “Finding the Right Model: The Joint Force, the People’s Liberation Army,” Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, April 24, 2023, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/Display/Article/3371164/finding-the-right-model-the-joint-force-the-peoples-liberation-army-and-informa/. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Xiao Tianliang, Kang Wuchao, and Cai Renzhao, “Science of Military Strategy,” China Aerospace Studies Institute, August 2020, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/documents/Translations/2022-01-26%202020%20Science%20of%20Military%20Strategy.pdf. ↩︎

Jeffrey Engstrom, “Systems Confrontation and System Destruction Warfare How the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Seeks to Wage Modern Warfare,” RAND Corporation, February 1, 2018, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1700/RR1708/RAND_RR1708.pdf. ↩︎

U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, “Chapter 8: China’s Evolving Counter-Intervention Capabilities and the Role of Indo-Pacific Allies,” in 2024 Report to Congress of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office, November 2024), https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2024-11/Chapter_8--Chinas_Evolving_Counter-Intervention_Capabilities.pdf. ↩︎

Lonnie Henley, “China Maritime Report No. 26: Beyond the First Battle: Overcoming a Protracted Blockade of Taiwan,” China Maritime Studies Institute China Maritime Reports, March 2023, https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports/26. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Sunny Cheung and Cheryl Yu, “Creative Destruction: PRC Undersea Cable Technology,” The Jamestown Foundation, January 16, 2025, https://jamestown.org/program/creative-destruction-prc-undersea-cable-technology/. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Australian Naval Institute, “China’s cable cutting theatre,” Australian Naval Institute, March 27, 2025, https://navalinstitute.com.au/chinas-cable-cutting-theatre/. ↩︎

Harrison Kass, “AC-31 Losharik: Russia’S Secret Spy Submarine Is ‘Out of Action’ Due to a Fire,” The National Interest, October 12, 2024, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/ac-31-losharik-russias-secret-spy-submarine-out-action-due-fire-213195. ↩︎

bno Chennai bureau, “Chinese Threat to Submarine Cables Emerges in Indo-Pacific,” February 27, 2025, https://www.bne.eu/chinese-threat-to-submarine-cables-emerges-in-indo-pacific-369355/. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Maritime Executive, “Chinese Freighter Suspected of Severing Telecom Cable off Taiwan,” The Maritime Executive, January 5, 2025, https://maritime-executive.com/article/chinese-freighter-suspected-of-severing-telecom-cable-off-taiwan. ↩︎

Charles Mok and Kenny Huang, “The Most Critical Resilience Questions of Them All: Taiwan’s Undersea Cables,” Taiwan Insight, October 2, 2024, https://taiwaninsight.org/2024/10/02/the-most-critical-resilience-questions-of-them-all-taiwans-undersea-cables/. ↩︎

Project 2049 Institute, “Undersea Cables: Taiwan’s Achilles Heel?,” Project 2049 Institute, April 28, 2010, https://project2049.net/2010/04/28/undersea-cables-taiwans-achilles-heel/. ↩︎

F. W. Lacroix et al., “A Concept of Operations for a New Deep-Diving Submarine,” report (RAND, 2001), https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA411748.pdf. ↩︎

Christine McDaniel and Weifeng Zhong, “Submarine Cables and Container Shipments: Two Immediate Risks to the US Economy if China Invades Taiwan,” Mercatus Center, August 29, 2022, https://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/submarine-cables-and-container-shipments-two-immediate-risks-us-economy-if. ↩︎

Philip Heijmans, “Should Taiwan Worry About Subsea Cable Security?,” gCaptain, October 27, 2022, https://gcaptain.com/should-taiwan-worry-about-subsea-cable-security/. ↩︎

Michael Matis, “The Protection of Undersea Cables: A Global Security Threat,” United States Army War College, March 7, 2012, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA561426.pdf. ↩︎

Joris Teer, Davis Ellison, and Abe de Ruijter, “The Cost of Conflict: Economic Implications of a Taiwan Military Crisis for the Netherlands and the EU,” The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, March 2024, https://hcss.nl/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Taiwan-The-Cost-of-conflict-HCSS-2024.pdf. ↩︎ ↩︎

Christopher Neely, “The Economic Effects of a Potential Armed Conflict Over Taiwan,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, February 2025, https://www.stlouisfed.org/-/media/project/frbstl/stlouisfed/publications/review/pdfs/2025/feb/economic-effects-of-potential-armed-conflict-over-taiwan.pdf. ↩︎

Robert Manning, “Would Anyone “Win” a Taiwan Conflict?,” Stimson Center, January 9, 2024, https://www.stimson.org/2024/us-china-taiwan-conflict-global-economy/. ↩︎

Joel Wuthnow et al., Crossing the Strait: China’s Military Prepares for War with Taiwan (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 2022), https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/Books/crossing-the-strait/crossing-the-strait.pdf. ↩︎

Yau-Chin Tsai, “The Influence of Matsu Undersea Cable Interruption on Taiwan’s National Defense Security,” INDSR Security Commentaries, no. 28 (August 28, 2023), Institute for National Defense and Security Research, https://indsr.org.tw/en/respublicationcon?uid=18&resid=2976&pid=5131. ↩︎

U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, “Chapter 4: A Dangerous Period for Cross-Strait Deterrence,” in 2021 Annual Report to Congress (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2021), https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2021-11/Chapter_4--Dangerous_Period_for_Cross-Strait_Deterrence.pdf. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Jared McKinney and Peter Harris, “Broken Nest: Deterring China From Invading Taiwan,” The US Army War College Quarterly Parameters 51, no. 4 (November 17, 2021): 23–36, https://doi.org/10.55540/0031-1723.3089. ↩︎ ↩︎

Gerard DiPippo and Jude Blanchette, “Sunk Costs: The Difficulty of Using Sanctions to Deter China in a Taiwan Crisis,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 28, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/sunk-costs-difficulty-using-sanctions-deter-china-taiwan-crisis. ↩︎ ↩︎

⁂